Heads-up: This blog is completely theoretical which helps for easy access and go through the concepts (acts as a revise book for you). A practical walkthrough of all these JWT attacks will be demonstrated in DeDefence YouTube channel. Stay tuned and make sure to subscribe.

- To prepare for AppSec interviews (Because it is most common topic which is often asked in every interview)

- Security Professionals

- Bug Bounty Hunters

- Developers

- QA

First Things First:

- Stripping the signature by manipulating the header algorithm to

none - Cracking weak

- Guessable secret keys used for signing

- Tricking servers into using the wrong algorithm (an “algorithm confusion” attack) to validate a forged token

Further risks arise from:

- Injecting malicious parameters into the token header to control the key verification process, potentially leading to path traversal, SQL injection, and the use of attacker-controlled keys.

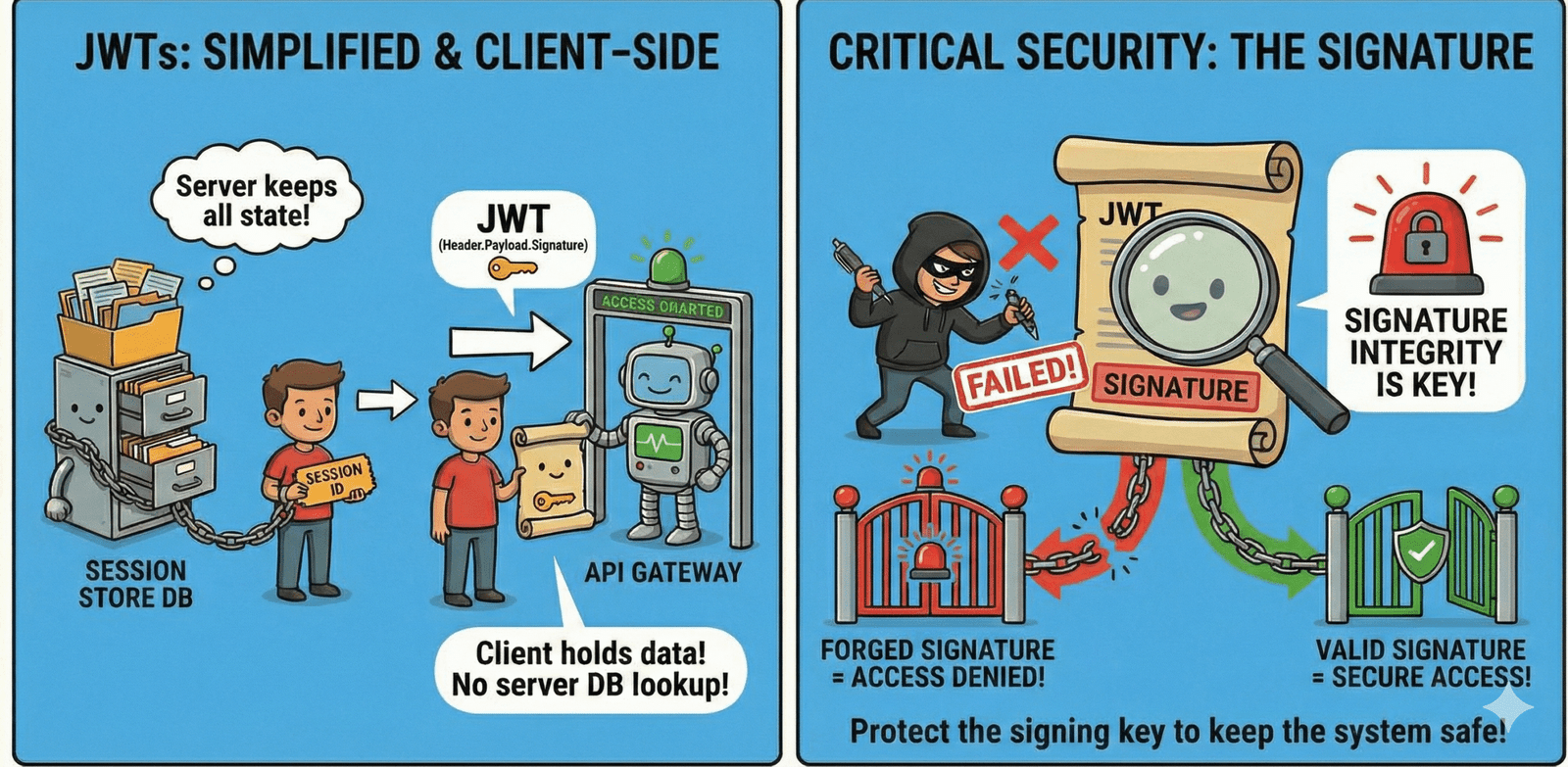

The Anatomy of a JSON Web Token (JWT)

The Three Parts of a JWT

.), each of which is Base64Url encoded.eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJzdWIiOiIxMjM0NTY3ODkwIiwibmFtZSI6IkpvaG4gRG9lIiwiaXNBZG1pbiI6ZmFsc2V9.EypViEDiJhjeuXgjtGdibxrFPFZyYKn-KqFeAw3c2Noalg: Specifies the cryptographic algorithm used to sign the token, such asHS256(HMAC with SHA-256) orRS256(RSA with SHA-256). This field is the source of several critical vulnerabilities.typ: Declares the token type, which is almost alwaysJWT.

- Registered Claims: Predefined claims like

iss(issuer),sub(subject),aud(audience),exp(expiration time), andiat(issued at). - Public Claims: Custom claims defined to avoid collisions, usually registered in the IANA JSON Web Token Claims registry.

- Private Claims: Custom claims created for information sharing between parties.

Titbits: The header and payload are only Base64Url encoded, not encrypted. And also keep in mind that the header and payload are Base64Url encoded/decoded not Base64 encoded/decoded. This means anyone who intercepts the token can easily decode and read its contents. Therefore, sensitive information like passwords, credit card numbers, or social security numbers should never be stored in a JWT payload.

- JWS (JSON Web Signature): The token is signed to ensure data integrity, but the payload is readable. It proves that the data has not been tampered with.

- JWE (JSON Web Encryption): The token’s payload is encrypted, providing confidentiality. The content is hidden from parties who do not possess the decryption key.

Titbits: JWT tokens can be implemented “path-wise” in the same domain. For example: JWT token 1 can be used in domain.com/profile, JWT token 2 can be used in domain.com/cart. So here two JWT tokens have been used for two different paths in single domain. So have a keen observation on implementation of JWT tokens in all the paths of the target domain.

The Attacker’s Playbook: Common JWT Vulnerabilities and Exploits

Attack 01: JWT Token Sent in GET Method

Vulnerability: Sending a JWT as a query parameter in a URL (e.g.,

example.com/api/data?token=eyJ...) instead of in a secure Authorization header. URLs are frequently logged by browsers, proxies, and web servers.Relatable Example: It’s like writing your house key code on the outside of the envelope you mail. Anyone who touches that envelope—the mailman, the sorting facility, or anyone looking over your shoulder—now has your key.

Exploitation Steps:

An attacker gains access to the victim’s browser history or a server access log.

They locate the URL containing the full JWT string.

The attacker copies the token and uses it to impersonate the user, gaining full access to their account without needing a password.

Mitigation: Always transmit JWTs in the Authorization Header using the

Bearerscheme. Ensure the application uses TLS/SSL (HTTPS) to encrypt the data in transit.

Attack 02: Improper JWT Token Expiration

Vulnerability: The token either lacks an

exp(expiration) claim or has a lifespan that is far too long (e.g., several days or weeks). If a token doesn’t expire quickly, a stolen token remains useful to an attacker indefinitely.Relatable Example: This is like a hotel room key card that never deactivates. Even after you check out, if someone finds that card a month later, they can walk right back into the room.

Exploitation Steps:

An attacker intercepts a user’s JWT through a Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) attack or Cross-Site Scripting (XSS).

Because the token has no expiration, the attacker can use it to access the system repeatedly over a long period.

Even if the user logs out, the “stolen” token remains valid because the server only checks the signature and the (non-existent) expiry date.

Mitigation: Set a short expiration time (e.g., 15 minutes) for access tokens. Use refresh tokens stored in

HttpOnlycookies to issue new access tokens safely.

Attack 03: Sensitive Information in JWT Payload

Vulnerability: Including private data like passwords, Social Security numbers, or internal server roles within the JWT payload. JWTs are encoded, not encrypted; anyone with the token can read the data inside using simple online tools.

Relatable Example: It’s like using a clear plastic briefcase to carry your private documents. Everyone can see exactly what is inside, even if the briefcase is “locked” (signed).

Exploitation Steps:

An attacker intercepts the JWT or finds it stored in the browser’s

localStorage.They paste the string into a tool like

jwt.io.The attacker reads the “hidden” sensitive data, such as the user’s home address or internal database IDs, which can be used for further social engineering or targeted attacks.

Mitigation: Only store non-sensitive identifiers (like a UUID or User ID) in the payload. If you must store sensitive data, use JWE (JSON Web Encryption) to ensure the payload is encrypted and unreadable to third parties.

Attack 04: Bypassing Signature Verification with the alg:none Attack

none algorithm, intended for situations where the token’s integrity has already been verified by other means. If a server’s JWT library accepts this algorithm, an attacker can completely bypass signature verification.- Vulnerability: The server trusts the

algparameter in the header—which is controlled by the attacker—to determine how to validate the token. By settingalgtonone, the attacker tells the server that no signature is present and the token should be considered valid as-is.

- Relatable Example: Imagine your office security pass has a field labeled “Verification Method: Biometric Scan.” An attacker scratches that out and writes, “Verification Method: Just Trust Me, Bro.” If the security guard sees this, shrugs, and lets them in without a scan, that’s the

nonealgorithm attack.

- Exploitation Steps:

- Capture a legitimate JWT.

- Decode the header and change the

algvalue tonone. Attackers often try multiple case variations (None,NONE,nOnE) to bypass naive string filters. - Decode the payload and modify claims, for example, changing

"isAdmin": falseto"isAdmin": true. - Re-encode the modified header and payload.

- Construct the new token by concatenating the parts and adding a trailing dot for the empty signature:

[new_header].[new_payload].. - Submit this forged token to the server. If vulnerable, the server will grant elevated privileges.

Attack 05: Cracking Weak HMAC Secrets (HS256)

HS256 is used, the security of the entire token rests on the strength and secrecy of the shared secret key. Developers sometimes use weak, default, or easily guessable secrets, making them vulnerable to offline brute-force attacks.- Vulnerability: An attacker with a single valid JWT has both the data that was signed and the resulting signature. This is enough to launch a dictionary or brute-force attack to find the secret key.

- Relatable Example: This is like setting your bank account PIN to “1234” or your computer password to “password”. An attacker doesn’t need to be a cryptographic genius; they just need a list of common passwords and a tool that can try them all very quickly.

- Exploitation Steps:

- Obtain a valid JWT signed with an HMAC-based algorithm (e.g.,

HS256). - Use a cracking tool like

hashcat(mode 16500) orJohn the Ripperwith a wordlist of common secrets (likerockyou.txtor JWT-specific lists). - The tool repeatedly signs the token’s header and payload with each secret from the wordlist and compares the result to the original signature.

- If a match is found, the secret is cracked. The attacker can now forge any token and sign it with the recovered secret.

- Obtain a valid JWT signed with an HMAC-based algorithm (e.g.,

Attack 06: Algorithm Confusion Attacks (RSA to HMAC)

RS256) but can be tricked into verifying with a symmetric one (HS256).- Vulnerability: An asymmetric

RS256token is signed with a private key and verified with a public key. A symmetricHS256token is signed and verified with the same secret key. If an attacker can change thealgheader fromRS256toHS256, a poorly implemented server might fetch the public key (which is not secret) and use it as theHS256secret for verification.

- Relatable Example: Imagine a high-security vault door requires a unique, secret physical key to lock (the private key), but its design can be verified with a publicly available blueprint (the public key). An attacker walks up, slaps a new label on the door that says “Standard Padlock,” and then uses the public blueprint to fashion a flimsy key. If the confused security system uses the blueprint to check the “padlock,” it will accept the forged key and open the door.

- Exploitation Steps:

- Obtain the server’s public RSA key. This can often be found at a

.well-known/jwks.jsonendpoint, in mobile app assets, or extracted from a TLS certificate. - Take a valid JWT and decode its header and payload.

- Change the

algparameter in the header fromRS256toHS256. - Modify the payload to escalate privileges (e.g.,

sub: "administrator"). - Sign the newly crafted token using the

HS256algorithm, providing the server’s public RSA key as the secret. - Submit the forged token. The server, expecting

HS256, will use its own public key to successfully verify the signature.

- Obtain the server’s public RSA key. This can often be found at a

Attack 07: Header Parameter Injection Attacks

kid(Key ID) Injection:Thekidparameter tells the server which key to use for verification, which is useful when multiple keys are in rotation. Attackers can abuse this if the server uses thekidvalue in an unsafe way.

- Path Traversal: If the

kidspecifies a file path to the key (e.g.,/var/www/keys/key123.pem), an attacker can inject path traversal sequences.- Example Payload:

"kid": "../../../../../dev/null" - Exploit: By pointing to

/dev/null, the server attempts to use an empty file as the verification key. The attacker can then sign their forged token with an empty string as the secret, resulting in a valid signature.

- Example Payload:

- SQL Injection: If the

kidis used to query a database for the key, it can be vulnerable to SQL injection.- Example Payload:

"kid": "' UNION SELECT 'attacker_controlled_key'--" - Exploit: The attacker tricks the database into returning a key they know, which they then use to sign their forged token.

- Example Payload:

- Command Injection: If the

kidvalue is passed into a system command, an attacker can inject malicious commands.- Example Payload:

"kid": "key.pem; whoami"

- Example Payload:

- Path Traversal: If the

2. jku (JWK Set URL) and x5u (X.509 URL) Injection: These parameters point to a URL where the server can fetch the key or certificate needed for verification.

- Vulnerability: If the server does not whitelist trusted domains, an attacker can host their own JSON Web Key (JWK) set or certificate at a URL they control and point the

jkuorx5uheader to it.

- Relatable Example: This is like asking a bouncer to check a guest list, but the guest provides a URL to a list they wrote themselves. If the bouncer doesn’t check who owns the website, they’ll accept the fake list.

- Exploit: The attacker generates their own public/private key pair, hosts the public key at their URL, modifies a JWT payload, and signs it with their private key. The server will fetch the attacker’s public key from the malicious URL and use it to successfully validate the forged token. This can also lead to Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) vulnerabilities.

jwk (JSON Web Key) Injection (CVE-2018-0114): This parameter allows a public key to be embedded directly into the token’s header.- Vulnerability: A vulnerable server will trust and use the embedded public key for verification without checking if it’s a known or trusted key.

- Exploit: An attacker generates their own key pair, embeds their public key in the

jwkheader, modifies the payload for privilege escalation, and signs the token with their corresponding private key. The server will validate the signature using the key provided by the attacker themselves.

Flawed Implementations: The Hidden Dangers

- Storing Sensitive Data in the Payload:As established, JWT payloads are merely encoded, not encrypted. Storing any sensitive data—personally identifiable information (PII), internal database IDs, detailed permission structures—creates an information disclosure vulnerability. This data can be read by anyone who obtains the token.

- Local Storage: Storing JWTs in

localStorageis common but dangerous. It is accessible via JavaScript, making tokens vulnerable to theft through Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks. A simple XSS payload can read the token from local storage and send it to an attacker’s server, leading to account takeover.

- Cookies: Storing JWTs in

HttpOnlycookies is significantly more secure, as it prevents JavaScript from accessing the token, mitigating XSS-based theft. Additional flags likeSecure(ensures the cookie is only sent over HTTPS) andSameSite(mitigates CSRF) should also be used.

- No Expiration (exp claim): A token without an

expclaim is valid forever. If stolen, it provides permanent access until the signing key is changed.

- No Revocation Mechanism: JWTs are stateless, meaning the server doesn’t track issued tokens. This makes revocation difficult. If a user logs out or changes their password, their old tokens remain valid until they expire. A robust system requires a server-side revocation list (a blacklist), which reintroduces a stateful component but is often necessary for security.

- Browser history.

- Web server logs.

- Proxy server logs.

- The

Refererheader when clicking links to external sites. - This significantly increases the risk of accidental leakage and theft. JWTs should be transmitted in the

Authorizationheader (e.g.,Authorization: Bearer <token>) or in secure cookies.

Tools of the Trade: The Pentester’s JWT Toolkit:

Tool | Primary Use | Description |

Manual Decoding & Forging | A web-based debugger for quickly decoding, verifying, and generating JWTs. Excellent for manual inspection. | |

Burp Suite Extensions | Integrated Proxy Testing | Includes extensions like JWT Editor (or JOSEPH) and JSON Web Token Attacker for seamless manipulation and attack automation within Burp Suite. |

All-in-One CLI Toolkit | A powerful Python script for checking validity, testing known exploits (like alg:none), cracking weak keys, and forging tokens. | |

Offline Secret Cracking | High-speed tools for brute-forcing HS256 secrets using wordlists and rule-based attacks. | |

Privacy-First Web Tool | A browser-based tool that performs all analysis locally, preventing token leakage to third-party servers. It checks for over 15 vulnerability types. | |

Data Manipulation | A versatile web-based tool for encoding/decoding, signing, and manipulating JWTs as part of a larger data processing workflow. |

JWT Security Best Practices and Mitigation:

- Use Strong Algorithms: Prioritize asymmetric algorithms like

RS256orES256over symmetric ones. Asymmetric keys prevent attackers from forging tokens even if they obtain the public key.

2. Use Strong Secrets/Keys:

- For HMAC (

HS256), the secret key must be long, random, and have high entropy (at least 32 bytes). Never use common words, defaults, or hardcoded values. - For RSA, use keys of at least 2048 bits.

- For HMAC (

3. Rotate Keys Periodically: Implement a key rotation policy to limit the window of exposure if a key is compromised.

4. Always Verify the Signature: This is the most critical step. Every token must be verified before its payload is trusted or used.

alg parameter from the header. Your server should be hardcoded to accept only one specific algorithm (e.g., RS256) and reject any token that specifies a different one. This is the primary defense against algorithm confusion attacks.exp: Ensure the token has not expired.nbf(Not Before): Ensure the token is not being used prematurely.iss: Verify that the token was issued by the expected authority.aud: Verify that the token is intended for your application.

kid, jku, or jwk. Use a whitelist of known, trusted key IDs and URLs.none algorithm or Psychic Signatures (CVE-2022-21449).- The best practice is to store JWTs in

HttpOnly,Secure, andSameSitecookies to protect against XSS and CSRF. - Avoid

localStorageorsessionStoragedue to XSS risks.

- The best practice is to store JWTs in

- Always use HTTPS.

- Pass the token in the

Authorizationheader, not in URL parameters.

THATS ALL !!! 🫡

Hope its relatable and helpful. This blog will be the go-to resource for many security enthusiasts, I make sure the content in this blog gets updated whenever there’s new attack / tool / approach came across.

For more don’t miss to follow DeDefence blogs and make sure to subscribe our Youtube Channel. All the best !!! 😎